Monday, October 17, 2011

Inner-city palimpsest. At the moment there's a new complex of Fender Katsalidis "lifestyle apartments" being built on the site of the former walk-up Housing Commission apartments on the block between Elgin Street, Nicholson Street, Canning Street and Palmerston Street, Carlton. The hoardings on the outside of the site boldly trumpet that whoever ends up living here will be "PROUD TO BE LOCAL".

This pisses me off for many reasons. First, it echoes the phrasing of "PROUD TO BE UNION" bumper stickers, and hence harnesses a mildly progressive and rebellious politics that is utterly at odds with the wealth and individualistic ethos that the owners of the apartments will likely possess.

Second, the new residents will be, by virtue of only just moving in, not local at all. If they're empty-nesting bourgie boomers, they'll probably have moved in from the suburbs. And if they're cashed-up international investors buying a pied-à-terre for their student children, they won't be locals either.

But most of all – most of all – I'm annoyed by the way this evocation of 'localism' completely elides the violence with which previous generations of 'locals' have been evicted and the spaces they called 'home' demolished. The Wurundjeri were the first people to call this place 'home'.

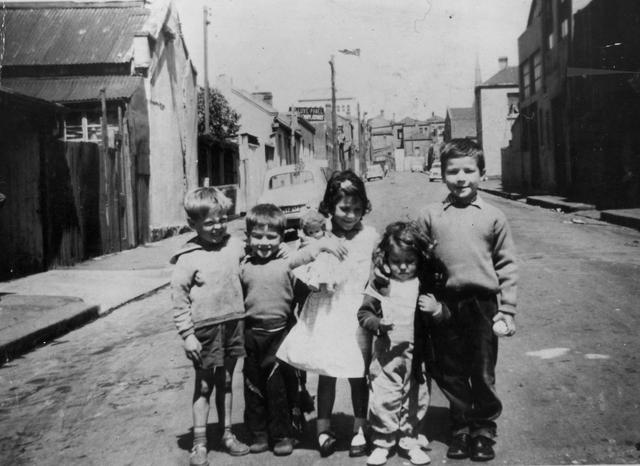

And by 1961, Carlton and Fitzroy were inner-city 'slums' targeted by 'slum clearance' programs. Atherton Street, Fitzroy, depicted in this photo, no longer exists: it's now part of the Atherton Gardens Commish.

The boy on the far left of the pic is Tony Birch, who set his novel Shadowboxing in the lost inner-city of his childhood. Birch also wrote a great essay about the duelling imperatives of slum clearance and bourgification that change both the streetscapes and the 'locals'.

The multicultured Commish residents who followed Birch's contemporaries have now been scattered and redistributed. There was a self-consciously therapeutic/rehabilitative public art project that took the form of interviews with the tenants who had to move, and photos of the space, things like: "I had to move my pot plants on the tram to Glenroy, one by one."

I remember being really angry with my mother, who never tires of mentioning in a slightly alarmed voice the proximity of the Commish to my house, and having a fruitless discussion with her that consisted of me going, "Poor people have a right to live close to the city as well, we're creating economic ghettoes," and her going, "Well isn't that what these flats are?"

Also, I was thinking about the death of the local pub and the fierce territorial response when pubs shut down or change, particularly the Champion Hotel which was a pivotal site for the 'Little Bands' scene in the '80s, and is now a post office. Or the Punters Club, or even the Tote.

It seems that people need certain urban spaces to enact their senses of belonging and social capital. And that's why any narrative of 'progress' that focuses on changing or renovating the spaces always seems traumatic and alienating.

But does socioeconomic alterity or displacement confer a kind of authenticity and legitimacy to one's relationship with inner-urban space? Am I being hypocritical in mourning the things that have been lost when my own bourgeois/bohemian tenancy in inner-city Melbourne is part of the problem? And am I over-romanticising 'space' when perhaps urban renewal actually opens up spaces for new and potentially exciting and iconic things to happen there?

It seems like there's a narrative of 'progress' with a counter-narrative of 'nostalgia', but as I argued at Crikey, nostalgia doesn't need to be retrogressive, but can also be progressive, reminding us of the valuable things we've been too short-sighted to remember.

This year at MIFF I watched two programs of short films about Melbourne, and I loved seeing various visions of a vanished Melbourne. But it was The City Speaks (1965) that I found most confronting. Produced by Crawford Productions for the Housing Commission at the height of the reforming moment, it disapprovingly tours various inner-city slum dwellings. Honestly, the cracked walls and back yards full of junk didn't look that bad. They reminded me of my own house.

Then it presents provocatively utopian visions of children playing in the first of Melbourne's new Commish estates. It's easy for a contemporary bourgie audience to ironise such sights, given that we think of Commishes as near-derelict crime traps rather than havens from slum poverty. But just recently, my mum was telling me about a BBC documentary she'd seen called Poor Kids, and how moving it had been to watch a poor family move into a new estate house and marvel at having two toilets, and both a front door and a back door. Perhaps the Commish was transformative for its early residents, even as it was destructive of the older modes of being a 'local'.

In a 2008 email exchange from which I've cribbed large chunks of this post, Ben Gook told me, "There were things involved in public housing -- political or ethical or moral commitments -- that are worth salvaging. The new book by Matthew Sharpe and Geoff Boucher argues that postmodernism has bestowed to both Right and Left a relativism that makes such commitments seem untrustworthy, old-fashioned. So not only is the articulation of these past ideas held to be quaint, the very act of even committing to a position in such a manner is held to be old-fashioned."

Indeed, another short film I saw, the modernist architecture manifesto, Your House and Mine, was a particularly fascinating artefact because of both its savagely satirical attitude to suburban home architecture and, as David Nichols notes, its relentless progressive momentum that comes across like a kind of blank-slate philosophy, never building on the past but aggressively erasing it. Early on, Robin Boyd's narration makes the startlingly shortsighted assertion that the founding of Melbourne in 1835 signified the "last days of the Aborigines”.

At any rate, we must recognise that no one group, at any one time, has the definitive and authoritative claim to be 'local'. Rather, places are palimpsests, constantly being overwritten but leaving tantalising traces of their past iterations behind.

And by 1961, Carlton and Fitzroy were inner-city 'slums' targeted by 'slum clearance' programs. Atherton Street, Fitzroy, depicted in this photo, no longer exists: it's now part of the Atherton Gardens Commish.

The boy on the far left of the pic is Tony Birch, who set his novel Shadowboxing in the lost inner-city of his childhood. Birch also wrote a great essay about the duelling imperatives of slum clearance and bourgification that change both the streetscapes and the 'locals'.

The multicultured Commish residents who followed Birch's contemporaries have now been scattered and redistributed. There was a self-consciously therapeutic/rehabilitative public art project that took the form of interviews with the tenants who had to move, and photos of the space, things like: "I had to move my pot plants on the tram to Glenroy, one by one."

I remember being really angry with my mother, who never tires of mentioning in a slightly alarmed voice the proximity of the Commish to my house, and having a fruitless discussion with her that consisted of me going, "Poor people have a right to live close to the city as well, we're creating economic ghettoes," and her going, "Well isn't that what these flats are?"

Also, I was thinking about the death of the local pub and the fierce territorial response when pubs shut down or change, particularly the Champion Hotel which was a pivotal site for the 'Little Bands' scene in the '80s, and is now a post office. Or the Punters Club, or even the Tote.

It seems that people need certain urban spaces to enact their senses of belonging and social capital. And that's why any narrative of 'progress' that focuses on changing or renovating the spaces always seems traumatic and alienating.

But does socioeconomic alterity or displacement confer a kind of authenticity and legitimacy to one's relationship with inner-urban space? Am I being hypocritical in mourning the things that have been lost when my own bourgeois/bohemian tenancy in inner-city Melbourne is part of the problem? And am I over-romanticising 'space' when perhaps urban renewal actually opens up spaces for new and potentially exciting and iconic things to happen there?

It seems like there's a narrative of 'progress' with a counter-narrative of 'nostalgia', but as I argued at Crikey, nostalgia doesn't need to be retrogressive, but can also be progressive, reminding us of the valuable things we've been too short-sighted to remember.

This year at MIFF I watched two programs of short films about Melbourne, and I loved seeing various visions of a vanished Melbourne. But it was The City Speaks (1965) that I found most confronting. Produced by Crawford Productions for the Housing Commission at the height of the reforming moment, it disapprovingly tours various inner-city slum dwellings. Honestly, the cracked walls and back yards full of junk didn't look that bad. They reminded me of my own house.

Then it presents provocatively utopian visions of children playing in the first of Melbourne's new Commish estates. It's easy for a contemporary bourgie audience to ironise such sights, given that we think of Commishes as near-derelict crime traps rather than havens from slum poverty. But just recently, my mum was telling me about a BBC documentary she'd seen called Poor Kids, and how moving it had been to watch a poor family move into a new estate house and marvel at having two toilets, and both a front door and a back door. Perhaps the Commish was transformative for its early residents, even as it was destructive of the older modes of being a 'local'.

In a 2008 email exchange from which I've cribbed large chunks of this post, Ben Gook told me, "There were things involved in public housing -- political or ethical or moral commitments -- that are worth salvaging. The new book by Matthew Sharpe and Geoff Boucher argues that postmodernism has bestowed to both Right and Left a relativism that makes such commitments seem untrustworthy, old-fashioned. So not only is the articulation of these past ideas held to be quaint, the very act of even committing to a position in such a manner is held to be old-fashioned."

Indeed, another short film I saw, the modernist architecture manifesto, Your House and Mine, was a particularly fascinating artefact because of both its savagely satirical attitude to suburban home architecture and, as David Nichols notes, its relentless progressive momentum that comes across like a kind of blank-slate philosophy, never building on the past but aggressively erasing it. Early on, Robin Boyd's narration makes the startlingly shortsighted assertion that the founding of Melbourne in 1835 signified the "last days of the Aborigines”.

At any rate, we must recognise that no one group, at any one time, has the definitive and authoritative claim to be 'local'. Rather, places are palimpsests, constantly being overwritten but leaving tantalising traces of their past iterations behind.