Sunday, April 15, 2012

Titanic Re-obsession 2012. Today, 15 April 2012, is the centenary of the sinking of RMS Titanic. Over the past few weeks I have been obsessed with the disaster and its surrounding myth-making and pop-cultural expressions, and documenting my obsession, in a self-loathing, ashamed way, on Twitter. A selection:

This New Yorker article by Daniel Mendelsohn is one of the best I've read about why Titanic still fascinates us, although this blog post by Chris O'Regan also has some intriguing ideas. O'Regan argues that the disaster appeals to us now because our own era-defining tragedies and errors are so diffuse, so out of our control. Perhaps our era is similar to the Edwardian one, he writes:

But Raise the Titanic makes the ship uncanny and sublime. The New Yorker's Mendelsohn likens the maiden ship to a woman:

(By the way, I can't watch the 'Part of Your World' scene from The Little Mermaid without imagining all the items salvaged from the Titanic wreck, exhibited and fetishised by the private company RMS Titanic, Inc.)

But the scene from Raise the Titanic in which the Titanic arrives in New York, while intended to be celebratory and triumphant, now seems deeply wrong and uncanny, especially as the Twin Towers are visible in the skyline. Again, I'm reminded of another film, this time Ghostbusters 2, in which the doomed vessel arrives as a ghost ship, spectral passengers disembarking through the iceberg's rent in the starboard side:

"Better late than never," the dock workers quip.

The reason I refer to my interest in Titanic as a 're-obsession' is that this is the latest cycle in a pre-existing obsession. I pored carefully over the National Geographic issue containing Robert Ballard's photos of the wreck. In 1997, I watched James Cameron's movie and was duly moved by its affective apparatus.

The thing about Cameron's Titanic is that it is so corny and obvious, from its treatment of class to its breathless protestations of love and beauty, and its gestures of tragedy and sacrifice. It is openly manipulative, yet there's also an innocent zest to it: a delight in both epic spectacle and small details and gestures.

Although many of these same themes can also be found in serious war epics and action movies, and indeed James Cameron's previous oeuvre, Titanic is commonly infantilised and feminised, its audiences portrayed as a ship of fools: sentimental teenagers and silly women, some of whom didn't even realise the sinking actually happened IRL.

At Jezebel, Lindy West admits to having adored it the first time around, but now, no longer being a teenager, "cannot for the life of me figure out why anyone would want to watch this movie—much less watch it in 3D."

It's striking how similar the blanket media coverage was to the coverage of contemporary tragedies such as 9/11: first dwelling morbidly on eyewitness accounts, and moving from those immediately affected to the lesser but equally sentimental participants, such as the animals on board. In recent years, coverage of the tragedy has turned melancholy as the last living survivors have died, lost to the oceans of time even though they had cheated the icy Atlantic in 1912.

Now, all we have are artefacts and documents to remind us that the ship carried individuals: people who struggled to live or were resigned to die, who had fascinating lives. A gay Washington insider. An indefatigable genre novelist. An interior decorator turned intrepid lady Indiana Jones.

But as a headline in the Toronto Star bluntly puts it, "In Titanic's roll of the dead, dogs were named, servants were not." There are even disagreements over how many people died in the tragedy. Some sources claim the toll is 1514; others 1517… for ease of reference, it's often capped at 1500.

To me it is profoundly melancholy that some people, like Titanic's Jack Dawson, can exist only in memory, and if forgotten can vanish as profoundly as if they had never existed at all. This thought makes me want to fight to document my life, as if by writing and blogging and tweeting and emailing I am flailing to stay afloat in cold, dark water.

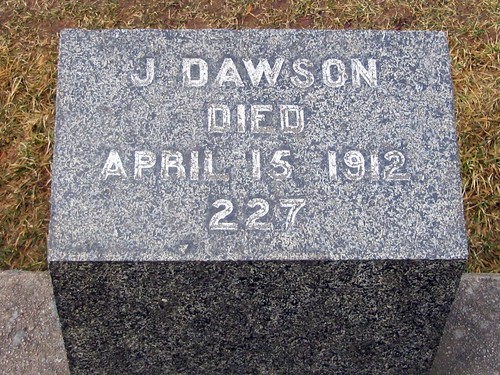

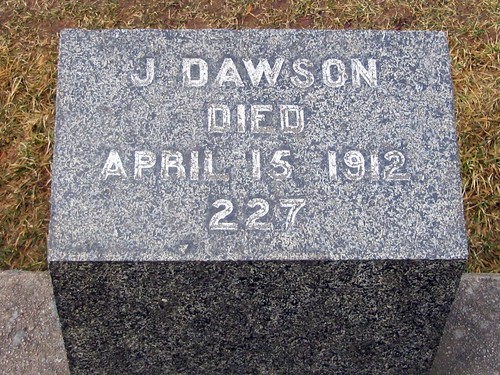

This headstone in a cemetery at Halifax, Nova Scotia, commemorates Joseph Dawson, who worked as a stoker on Titanic. His was the 227th body recovered from the site. Many headstones carry no names, but the stones are still tangible reminders of the disaster's human dimension.

Right now I'm also watching Mad Men, another story about the clash between individuals and the weight of history. Like Rose DeWitt Bukater, swimming free of her unwanted old life and surfacing as Rose Dawson, Dick Whitman used the Korean War to become Don Draper, who went on to sell the euphoria of self-transformation to the American public through the promises of advertising.

I can just feel I'm going to descend into the depths of a major 'Titanic' jag ahead of its forthcoming cinematic re-release.

— Mel Campbell (@incrediblemelk) February 22, 2012

First sign of 'Titanic' re-obsession: my new butterfly hair clip. (ps it is v.hard to photograph back of yr own head) twitter.com/incrediblemelk…

— Mel Campbell (@incrediblemelk) March 16, 2012

Guys, I can feel myself *sinking* into 'Titanic' Re-Obsession 2012. Done Stage 1: Rewatch movie in 3D. Now on Stage 2: Obsessive Wiki study.

— Mel Campbell (@incrediblemelk) March 21, 2012

Getting stuck in a vortex of 'Titanic' costume fandom. Wondering if they think of themselves as Edwardian re-enacters or film cosplayers?

— Mel Campbell (@incrediblemelk) March 24, 2012

'Titanic' Re-Obsession 2012 continues: doncha reckon the 1794 painting 'Pinkie' looks like Kate Winslet's 'swim' dress? bit.ly/GMx4yD

— Mel Campbell (@incrediblemelk) March 24, 2012

OVERWHELMED BY 'TITANIC'-RELATED #FEELINGS. Almost want to pitch a story on this but must focus on book. How can I put this in the book?

— Mel Campbell (@incrediblemelk) March 24, 2012

Making a cup of tea, crooning the opening song from 'Titanic'. bit.ly/HkQ3Uw I probably shouldn't tweet this lame shit, but #feelings

— Mel Campbell (@incrediblemelk) March 28, 2012

It's a terrible sickness: I just saw the word ICONIC and read it as TITANIC. #titanicreobsession2012

— Mel Campbell (@incrediblemelk) April 6, 2012

Céline Dion ft. The Lonely Island: I'm On A Titanic [Explicit]: bit.ly/HPuBaI #titanicreobsession2012

— Mel Campbell (@incrediblemelk) April 13, 2012

This New Yorker article by Daniel Mendelsohn is one of the best I've read about why Titanic still fascinates us, although this blog post by Chris O'Regan also has some intriguing ideas. O'Regan argues that the disaster appeals to us now because our own era-defining tragedies and errors are so diffuse, so out of our control. Perhaps our era is similar to the Edwardian one, he writes:

"Globalisation, new and strange philosophical and scientific thought, changing modes of production, boom-bust economics, new technologies, new media, geopolitical instability, and the ferment of upheaval taking place behind a facade of political and social institutions that seem so outwardly unchanging and old and stable."The sight of the intact Titanic breaching the surface and being towed into New York in the 1980 movie Raise the Titanic is preposterous. We now know, in remorselessly forensic detail, that the ship languishes on the seabed, broken violently in half like a banana, in an odd tension between preservation and destruction. It is still a marvel of culture and engineering, with so much of its fitout still startlingly recognisable; yet it is also a fragile relic crushed and eroded by deep-sea pressures, currents and anaerobic bacteria. The wreck may not withstand another century.

But Raise the Titanic makes the ship uncanny and sublime. The New Yorker's Mendelsohn likens the maiden ship to a woman:

"Like Iphigenia, the Titanic is a beautiful 'maiden' sacrificed to the agendas of greedy men eager to set sail; the forty-six-thousand-ton liner is just the latest in a long line of lovely girl victims, an archetype of vulnerable femininity that stands at the core of the Western literary tradition."Here, her otherworldly emergence, prow first, from the sea, carries a sublime, almost sexual pleasure. It is a spectacle for the male gaze, like Honey Rider in Dr No, or Ariel in The Little Mermaid:

(By the way, I can't watch the 'Part of Your World' scene from The Little Mermaid without imagining all the items salvaged from the Titanic wreck, exhibited and fetishised by the private company RMS Titanic, Inc.)

But the scene from Raise the Titanic in which the Titanic arrives in New York, while intended to be celebratory and triumphant, now seems deeply wrong and uncanny, especially as the Twin Towers are visible in the skyline. Again, I'm reminded of another film, this time Ghostbusters 2, in which the doomed vessel arrives as a ghost ship, spectral passengers disembarking through the iceberg's rent in the starboard side:

"Better late than never," the dock workers quip.

The reason I refer to my interest in Titanic as a 're-obsession' is that this is the latest cycle in a pre-existing obsession. I pored carefully over the National Geographic issue containing Robert Ballard's photos of the wreck. In 1997, I watched James Cameron's movie and was duly moved by its affective apparatus.

The thing about Cameron's Titanic is that it is so corny and obvious, from its treatment of class to its breathless protestations of love and beauty, and its gestures of tragedy and sacrifice. It is openly manipulative, yet there's also an innocent zest to it: a delight in both epic spectacle and small details and gestures.

Although many of these same themes can also be found in serious war epics and action movies, and indeed James Cameron's previous oeuvre, Titanic is commonly infantilised and feminised, its audiences portrayed as a ship of fools: sentimental teenagers and silly women, some of whom didn't even realise the sinking actually happened IRL.

At Jezebel, Lindy West admits to having adored it the first time around, but now, no longer being a teenager, "cannot for the life of me figure out why anyone would want to watch this movie—much less watch it in 3D."

"All of the characters are either 15-year-old girls in disguise ('Parents just don't understand!' 'Waaah, make the boat go faster!' 'I know we literally met 20 minutes ago, but I love you with a suicidal fervor!'), or the kind of goofy caricatures that 15-year-old girls would write if we let 15-year-old girls write our blockbuster screenplays."But part of what has driven my Titanic Re-obsession 2012 is the pathos of individual lives versus the inexorable heft of history. The sinking of Titanic was the first major news story to hinge on communications technology. A potential rescue ship, the Californian, did not respond in time because its telegraph room was not manned overnight; meanwhile, news of the disaster reached New York via telegraph before the survivors did.

It's striking how similar the blanket media coverage was to the coverage of contemporary tragedies such as 9/11: first dwelling morbidly on eyewitness accounts, and moving from those immediately affected to the lesser but equally sentimental participants, such as the animals on board. In recent years, coverage of the tragedy has turned melancholy as the last living survivors have died, lost to the oceans of time even though they had cheated the icy Atlantic in 1912.

Now, all we have are artefacts and documents to remind us that the ship carried individuals: people who struggled to live or were resigned to die, who had fascinating lives. A gay Washington insider. An indefatigable genre novelist. An interior decorator turned intrepid lady Indiana Jones.

But as a headline in the Toronto Star bluntly puts it, "In Titanic's roll of the dead, dogs were named, servants were not." There are even disagreements over how many people died in the tragedy. Some sources claim the toll is 1514; others 1517… for ease of reference, it's often capped at 1500.

I'm having #feelings about 'Titanic'. Thinking about all the people like Jack, whose lives leave no trace in history.

— Mel Campbell (@incrediblemelk) March 21, 2012

To me it is profoundly melancholy that some people, like Titanic's Jack Dawson, can exist only in memory, and if forgotten can vanish as profoundly as if they had never existed at all. This thought makes me want to fight to document my life, as if by writing and blogging and tweeting and emailing I am flailing to stay afloat in cold, dark water.

This headstone in a cemetery at Halifax, Nova Scotia, commemorates Joseph Dawson, who worked as a stoker on Titanic. His was the 227th body recovered from the site. Many headstones carry no names, but the stones are still tangible reminders of the disaster's human dimension.

Right now I'm also watching Mad Men, another story about the clash between individuals and the weight of history. Like Rose DeWitt Bukater, swimming free of her unwanted old life and surfacing as Rose Dawson, Dick Whitman used the Korean War to become Don Draper, who went on to sell the euphoria of self-transformation to the American public through the promises of advertising.

Comments:

<< Home

Arthur C Clarke's novel 'The Ghost from Grand Banks' (which I bought in, of all places, Woolies) is about another such attempt to raise the Titanic. It fails, and the end of the novel has a poignant coda in a far distant SF future, when mankind has long left the earth, but the Titanic continues decaying away on the bottom of the ocean.

Post a Comment

<< Home